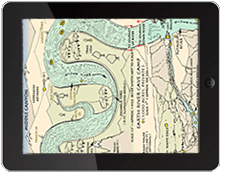

The dam that troubles Mukash—if it is ever built—would be the linchpin of the Great Whale complex, just one part of the gigantic James Bay hydroelectric project. Sponsored by Hydro-Quebec, a quasi-government utility, the project has been abuilding for 20 years. Its first power plant—the largest underground generating station in the world—was completed on the La Grande River in 1982; three others have since been commissioned, and work has begun on four more. Three great rivers—the Eastmain, Opinaca, and Caniapiscau— were diverted to feed the 500-mile-long La Grande, doubling its mean annual flow and increasing its winter flow by a factor of eight. In the resulting trade-off the Eastmain was parched to a trickle.

So far, Hydro-Quebec has invested more than 21 billion dollars (16.3 billion dollars U. S.), built five wilderness airports, strung at least 5,000 miles of transmission lines through forest and wetlands, consumed more than 1.6 million tons of fuel, and blasted out and redistributed a volume of rock fill sufficient, in the words of the utility's literature, "to build the Great Pyramid of Cheops 80 times over."

And this is only for starters, because if and when all the elements of the James Bay project are ever in place, a territory the size of Montana will embrace no fewer than 30 major dams and 500 separate dikes, while impounding reservoirs that in aggregate surface area would equal Lake Erie. And there would be generating capacity to crank out a volume of megawatts exceeding that of all the major U.S. hydro dams in the Columbia and Colorado River basins combined.

In the view of Hydro-Quebec and the provincial government, power of this magnitude provides jobs for the jobless, industrial growth, political stability. And it all flows out of a place so remote and sparsely settled that it hardly seemed necessary for Hydro-Quebec to consult the indigenous population, the Cree and the Inuit much less expect that many of these people would view the project not as a triumph of engineering but as a threat to their way of life.

Drifting down the Great Whale in the August twilight, I find it difficult to imagine this country bristling with development and easy to share the Cree's concern. I have seen enough of the river—tasting its spray in quieter rapids, walking around the rowdy ones, flying over the watershed's multitudinous lakes and streams—to know that this is wilderness as wild as any is ever likely to be.

The Great Whale complex would take this tumbling 225-mile-long river and, with dams and dikes, convert much of its length into a series of artificial slack-lakes. These reservoirs would submerge more than a thousand square miles of riverine lands and untamed waters. There would be three big generating stations, an all-season road linking the Great Whale River and Whapmagoostui—now unreachable except by air or sea—with tamer precincts to the south, more work camps, more airports, more Cheopses.

True, there is an airport already at Whapmagoostui. The Cree possess snowmobiles and outboard motors, modern housing, telephones and television, plumbing, and—click!—electric lights. But a little comfort and convenience clustered at the snout of the Whale cannot alter the big wildness still intact in its belly or so quickly dull the racial memory of a time when all Cree lived in the bush. Only the James Bay project could do that.

In 1973 the Cree won an injunction to stop construction of La Grande projects, only to see that ruling over turned by the Quebec Court of Appeal. The court found that, since construction had already begun, a "balance of convenience" favored Hydro-Quebec; that the nearly 10,000 Cree who occupy the area lacked clear rights in the territory, inasmuch as Charles II of England had granted exclusive rights to the Hudson's Bay Company in 1670; and that hydro development would not harm the environment but likely improve it. Stunned, the Cree sat down to negotiate.

From the bargaining table came a massive document, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, signed in 1975 by the Canadian government, the Province of Quebec, the Cree, and the Inuit (whose communities lie mostly to the north of the project area). In effect the agreement permitted completion of the La Grande power plants, compensated the Cree and Inuit with money packages totaling 225 million dollars, and promised them the right to govern, hunt, fish, and trap on their traditional lands. Hydro-Quebec retained wide latitude in assessing and managing the impact of its projects.

But from the Cree perspective the social and environmental impact of the La Grande development would prove to be substantial. So when the project's next major installment surfaced in the Great Whale complex, the Cree argued that it was not explicitly authorized by the 1975 agreement and, in no uncertain terms, warned that they'd have no part of it.

Radisson is a Hydro-Québec company town. For nonnative Quebecers, it is the project area's capital city. Located only a few miles from the largest of the La Grande power plants, the community provides for hundreds of people who keep the company's north country infrastructure in working order.

Radisson derives its name from the 17th-century French explorer Pierre Esprit Radisson, while the town's main street, des Groseilliers, honors his fur-trading partner. "We were Caesars," wrote Radisson, satisfied that in the wilderness there was "nobody to contradict us."

The venerable Radisson name is also attached to the project's principal substation nearby. When the wires started humming in 1979, Quebecers living in the province's towns and cities heated their homes mostly with oil or gas. But within a decade hydropower, delivered at favorable rates, had doubled the percentage of all-electric homes in the province—to 63 percent. Including industrial and commercial users, overall demand for electricity was up by 60 percent.

In fact, for a while in the 1980s it seemed as if Hydro-Quebec's customers couldn't keep up with all the river water spinning those turbines along the La Grande. So, to avoid simply spilling that water over the dams, as well as to hurry along Quebec's coming of age as an industrial power, government and utility officials unrolled a welcome mat along the St. Lawrence River Valley for aluminum and magnesium smelters. Both require prodigious infusions of electricity. It now takes the energy equivalent of an entire Great Whale complex just to supply the half dozen metals manufacturers that responded to Quebec's invitation and the utility's contractual generosity with flexible rates.

One day in Montreal, I called on Pierre Bolduc, Hydro-Quebec's executive vice president for marketing and international affairs. Bolduc said that the welcome mat was no longer out for more metal-smelting operations. But he predicted that once the economy began to improve, "aggressive industrial development" would resume in high-energy sectors other than metals—in the conversion of Quebec's older pulp and paper mills from chemical manufacturing processes to state-of-the-art electromechanical ones and in the supercharged environmental control technologies of the 21st century. Hydro-Quebec is figuring on a total growth of 525 to 600 megawatts a year.

Last year New York State backed out of an agreement to import a thousand new megawatts from Hydro-Quebec's grid, but other contracts are still in effect with northeastern U. S. customers, and these draw off 6 percent of Quebec's installed hydroelectric capacity. Bolduc explained why export contracts are essential to a growing Quebec:

"It is like having the need to house your family. Today the children are young and sleep in the same room. But you know that some day they will need more space. So you add a floor to the house, and it is just as easy to build five rooms as three. And until the children are older, you rent their rooms out to help pay off the mortgage."

In the Bolduc analogy then, the James Bay project is the house that Quebec built, the La Grande complex one of its floors, and the Great Whale complex another floor one flight up. And now a third floor is proposed for the 21st century. It is the NBR complex. It would divert the Nottaway and Rupert Rivers into the Broadback, increasing its mean annual flow sevenfold, and, with at least nine major dams, flood an area twice as large as that to be submerged by the Great Whale complex. But will Hydro-Quebec ever build the NBR?

"I'm not too sure," Bolduc told me that day in Montreal. "There are more environmental variables in the NBR area than on the Great Whale. Still, it's an option."

Matthew Coon-Come, a wiry, impassioned young man from the village of Mistassini, is Grand Chief of the Grand Council of the Cree, and while he views the James Bay project as a "massive attack on Cree territory," he also knows that his people cannot freeze their ways forever in the past. But outsiders, he says, "are dictating the pace of change without giving us the opportunity to adapt. Other societies have had a hundred years or more to get ready for change. We are being forced to do it in 20."

Of all the changes in the north country, the most threatening in the Cree's perspective are those affecting their sources of traditional foods. A kind of spiritualism is attached to their quest for wild foods; hunting, fishing, and trapping not only feed the stomach but also nourish the soul.

One can therefore appreciate the Cree's consternation when, in the early 1980s, the word went out that they should sharply restrict their voracious appetite for fresh water fish, such as pike and lake trout, because levels of methylmercury, a neurotoxin, had increased through the decay of vegetation flooded by the reservoirs of the La Grande complex. Hydro-Quebec officials concede that some species of fish in their reservoirs turned up with concentrations of methylmercury five times as high as those occurring in natural lakes in the region. While there have been no acute cases of mercury poisoning in any native community in the James Bay area, fears remain nonetheless.

The Cree are likewise concerned about caribou. Cree say that the La Grande reservoirs have destroyed some of the best caribou feeding areas in the north country and that the Great Whale impoundments will destroy many more. Hydro-Quebec officials claim that the reservoirs may actually be beneficial to migrating caribou in the winter time—wide expanses of ice could make the migrating easier and keep the animals safer from predators.

In 1991 the Cree won a court judgment ordering Ottawa to initiate an environmental-impact assessment of the hydroelectric project proposed for the Great Whale River. The guidelines for that review, raising hundreds of separate issues that Hydro-Quebec must address, were completed last year by joint panels of Cree, Inuit, provincial, and federal officials. A final environmental-impact statement is expected by the end of this year. While much of this assessment will surely focus on impacts most closely associated with the welfare of the Cree and Inuit, there are also issues of national, and possibly global, concern.

The marine ecology of James and Hudson Bays has only recently come under close scrutiny. Balances are finely tuned in the subarctic. Much of the marine food chain depends on spring blooms of ice algae and phytoplankton, which in turn rely on a delicate blend of fresh and salt water. Shift the blending time or alter the mix, and you may well be disrupting an aquatic commissary supplying Cree or Inuit hunters who come from hundreds of miles away.

And finally there is concern about the cumulative impact of hydroelectric development on the entire Hudson Bay region and even beyond, off the Labrador and Newfoundland coasts. Manitoba has dams. diversions. and altered flows on the Churchill and Nelson Rivers, and a palpable itch to develop the Gods, Hayes, and Seal as well. Ontario has plans to redevelop dams on one of its bay-bound rivers. If the La Grande complex is suspected of upsetting nutrient and salinity balances offshore, what happens when you throw Great Whale, NBR, and all the dammed rivers of Manitoba and Ontario into the bargain? How will this affect the ecological flux of the bays, the Arctic char, the beluga whale, the bearded seal, the Canada goose, the Cree, the Inuit, even the fishermen of Newfoundland?

In Montreal, I put that question to Jean-Francois Rougerie, environmental project manager for the Great Whale complex.

"Yes, this is something we are concerned about," said Rougerie. "But so far, all the effects that we can measure remain local."

And I said, "Are you saying then, that if most of the rivers around James and Hudson Bays were developed the way the La Grande has been developed, there would be no major impact on the marine ecosystem of the two bays or on some place beyond them?"

"Based on the information we have now," said Rougerie, "that would be our conclusion. No major impact."

Hearing that, I thought suddenly of old Pierre Radisson, breaking the ice for a North American fur trade and confident as a Caesar because, in the wilderness, there was no one to contradict him.

Note: Later that same year Eric Hertz convinced the New York Times to come up and do a feature in their Sunday Magazine section. New York was slated to be the main purchaser of the James Bay power. Although it was too late in the season for the Times to run the river, they spent a week with the Cree community and wrote a scathing article condemning the project.