For many years this region was off-limits to outsiders. Only recently have Chinese officials relaxed control, sensing perhaps the public relations value in allowing expeditions to discover its striking wilderness. Truth is, the chance to make a first recorded descent, rather than the majestic scenery, has drawn me here. Fewer and fewer rivers in the world have never been run. Yet first descents are risky. Once on the river, our biggest concern is getting trapped in one of the many canyons. If anyone gets badly injured, help will be out of the question. Chinese officials forbid us to carry radios.

As the organizer of our trip, Eric has been losing sleep over such worries.

We reach the Shuiluo at noon on October 20, 1995, after a year of planning and three days of hard driving from Dayan (Lijiang), a prosperous frontier city of 39,000 in northern Yunnan Province. The rainy season has ended, and golden poplars climb the hills as we drive to where we put in, about 80 miles above the Shuiluo's juncture with the Yangtze. This is the first navigable section accessible by road. We pass blue trucks loaded down with logs, and yaks carrying freshly cut kindling.

“It's more water than I hoped for,” says Joe Dengler, frowning at the deep blue waters rushing by. A descendant of a scout on the Lewis and Clark expedition, Joe is our team leader on the river. Six feet tall with short black hair and blue eyes, the 30-year-old guide from California is hard as an ax handle but gentle in spirit. He estimates the flow as 1,200 cubic feet per second—20 percent more water than we'd expected. The stretch of the Shuiluo we're running drops 3,000 feet before joining the Yangtze, but we don't know whether it descends gradually or in a series of steep waterfalls.

We've brought two kayaks, two 14-foot rafts, two 12-foot Shredders (black pontoons connected by a rubber floor), and a 16-foot "cataraft" (two yellow pontoons attached by an aluminum frame). There are 18 of us, half professional river guides and half experienced amateurs. We're taking food and fuel for ten days as well as ropes and gear to climb out if necessary.

It's late afternoon by the time we paddle away from shore. Children chase us along a trail beside the river, racing past white prayer flags on poles. For the next two hours we ride gentle rapids, then stop to make camp. A local hunter has told our Chinese teammate, Zhang Jiyue, that a waterfall waits just ahead. Jiyue is not worried. What looks like a waterfall to the hunter may be a rapid we can easily run. But we are all concerned by how slowly the river is dropping. It means there are big falls ahead—somewhere.

Late the next day, just past a tributary that nearly doubles the volume of the river, we enter a deep gorge where the water picks up steam. As ebony granite walls rise 200 feet on either side of us, I realize there's no place to pull over. Ahead the river disappears to the right into blackness. I can hear the roar of a big, big drop. Just like that—in less than a minute—our worst fear has been realized. We're trapped in a canyon with no escape but downriver.

Determined not to round the corner blindly, Joe steers our boat to the right side of the river, where I grab onto the slick wall. As I cling to the granite with my fingernails, Joe climbs 20 feet straight up the cliff to scout ahead.

“Looks like the river turns hard right, then goes left over a ten-foot drop,” Joe shouts over the roar.

“We've got to hug the right wall, then paddle straight over a big rock. We can't allow the boat to be sucked left!” If we do, the river's powerful hydraulics will yank it under, tossing us all into the river. The other boats stack up behind us, rafters paddling furiously against the current, as we head into the violent rapids. Grunting and groaning, we sink our paddles deep into the froth, trying desperately to keep to the right. As we drop over the waterfall, the front of our raft gets sucked under, burying all five of us at once. It feels as if somebody has dumped a swimming pool on top of our heads. We keep paddling and pop out like a cork at the bottom of the rapid, where we pull into a shallow alcove. Eric's Shredder, taking the same plunge, flips as soon as it hits the big drop. "They're over," shouts Marco Gressi, one of our two scouts, paddling his kayak 60 feet below the rapid.

Eric and his raft mate, Henry Black, are tossed into the water, which churns like a washing machine. From down river the kayakers can see Henry's orange helmet bobbing, his eyes wide open, arms striking out for the walled shore. Eric is trapped at the bottom of the waterfall beneath an overhang. In high school Eric was a champion wrestler, but nothing has prepared him to fight a waterfall.

As Eric struggles, the second Shredder enters the rapids and flips, landing almost on top of him. One paddler clings to the boat, while another struggles toward the slick wall. Now we've got four swimmers.

“Grab him!” Marco shouts as Henry floats past the first raft. A rafter reaches out to pull him in but can't. The river is too swift. Seeing him drift almost out of reach, Beth Rypins, a river guide from San Francisco, makes a last stab over the stern, seizes him by the life jacket, and wrestles him into the raft. The next swimmer floats by, hanging on to the overturned Shredder. Then Eric and another teammate appear, looking like waterlogged cowboys riding the other Shredder.

We are all safe for now. But it's getting dark, and we can't stay here. As soon as we push away, however, we come upon another blind turn 60 feet downriver. We steer back toward the right wall and grab onto the rock again. Joe and Beth climb above us for a look.

“No problem,” Joe says. “Just one big drop.” His words ring hollow. I've seen Joe in enough tough spots to know he isn't telling us the whole story. He gives me a tight smile and tugs on his helmet strap:

“Paddle hard, but be ready to throw your weight to the center if we drop off something big.”

The next half hour is terrifying as we run one Class V rapid after another (on a scale where Class VI is virtually unrunnable). Rounding turn after turn, we run smack into six-foot waves. Finally, about 7 p.m., we spot a rockslide on the right, where we pull out for the night. Exhausted and cold, we haul our boats onto the rubble. There isn't a flat spot in sight. Not wanting to carry extra weight, we haven't brought tents. We unroll our sleeping bags onto sharp rocks. Dinner for 18—freeze-dried noodles—is prepared over a small propane stove. Our mood is as dark as the moonless night.

"We couldn't see a damn thing,” Joe admits over our meal. “But what could we do? We had to run it.”

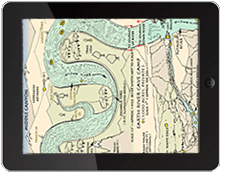

“Man, I'm lost,” Joe grumbles on day three as he studies one of our maps, a muddy photocopy of a 1948 Russian topographical map.

“If I'm right, we should hit a flat section soon where we can make up some time.”

No such luck. As soon as we emerge from the steep gorge that just tried to swallow us, we find ourselves facing a half mile of rock-choked canyon. Boulders as big as mobile homes block the middle of the river, followed by two waterfalls beyond, one tumbling 15 feet, the other 20.

Beth, Joe, and a few others hike down past the lower falls and toss a couple of small logs into the waves. The logs submerge instantly, disappear for 30 seconds, then shoot back up, minus the bark, into the cauldron of white water.

"They didn't plan those rocks well, did they?" Beth says. It takes Joe only ten minutes to decide this stretch is unrunnable. Moving gear around the rapid, however, takes us nearly all of day four. We're still 55 miles from the Yangtze, and our kayakers, scouting ahead, report another stretch of boulders in our path. “It's even worse than before,” Marco says.

Pushing and pulling our boats along the rocky left shore of the river, we reach a 40-foot waterfall where the river disappears into a narrow canyon—certain death for anyone swept inside. There's no room to hike farther on the left side. We'll have to cross the river. That night we make camp less than half a mile from where we spent the night before. None of us sleeps well.

Sitting stiffly on the cold bank of the river as dawn breaks, I sip warmed-up goat stew and watch a flock of starlings slowly rise into the sky, their wings silvered by the morning's brightness. Pillowy clouds hover over the golden peaks as a single shaft of sunlight spotlights the forested slopes. Joe and Eric have come up with a plan. Paulo Castillo and Joe will carry a 200-foot-long rope to the other shore on Paulo's cataraft, the only large boat nimble enough to keep from being swept over the waterfall.

A white-water rafter since he was a teenager, Paulo is more at home on the water than off. As he prepares his gear, Paulo changes from sandals to running shoes, a sure sign he's taking the crossing seriously. I've never seen him wear sneakers on the river before.

“As soon as we bump the rocks on the other side, jump off and pull us in,” he tells Joe. “I don't want to have to make the approach twice.”

With a big push, the pair launch the cataraft into the crystal blue water, and Joe mounts the bow like a bronco rider, gripping the frame with one hand, a red-and-yellow rope slung over his shoulder. The pulsing current pulls the boat down the left side—the wrong side. But with a half dozen strong strokes, Paulo propels the craft across the lip of the falls and into the rock-laden eddy on the opposite shore. Joe leaps off, stumbles briefly, then pulls the cataraft to safety. We all whoop with relief.

Though it has seemed like hours, the nerve-racking crossing has taken all of 20 seconds. We spend the rest of the morning rigging ropes and pulleys to pull the rest of us across the river.

Once we're together again on the right side, we begin a two-hour portage-from-hell around the falls, climbing boulders and hacking through the brush along the shore. In the midst of our labors, we discover a human body draped over a log crammed between two rocks. The back of the man's head was fractured, his shirt stripped away by the rushing water. He must have gotten too close to the river during the spring melt down and been swept away. Tanya Hrabal, one of the team's two physicians, estimates that he has been dead for several months. We soon find two more victims of the same fate.

We begin day six with a sense of euphoria—the sun is bright, the rapids are runnable, and the canyon is starting to widen. But shortly after noon we hit yet another steep drop that requires pushing the boats up and over 20-foot-tall boulders. We camp alongside a long, unrunnable rapid squeezed between a field of rocks and a wall. That night by a roaring fire Joe announces to the group that he and Eric, as the trip's leader and organizer, have decided to end our journey at the next village, one or two days away, 30 miles short of the Yangtze. Three thousand feet above the village is a supply depot and a road, he says, the last place for us to hike out. From there, we can hitchhike to Dayan. “I know you're all disappointed that we won't be dipping our toes in the Yangtze,” Joe says. “But if we hit another gorge, it could take us ten days to finish, and we're running out of time and supplies.”

It's a difficult decision to accept.

“I've never quit anything I've ever started," says Jon Dragan, a seasoned guide from West Virginia. “I agree,” says Henry Black, a veteran rafter from California. “You don't get many opportunities in life to go into the unknown. I think we should keep going.”

I'm tempted to argue for staying too, but I know that we are exhausted and several of us are quite sick.

“None of us wants to die on this river,” Eric argues. “We were lucky to have survived the first gorge. We might not be so lucky a second time.”

The following day is the most fun, running Class III and IV rapids under a hot sun as the valley spreads out on both sides. We stop for lunch on a broad beach opposite a small gold mine. A surprise to us all, at day's end we arrive at the bridge that will lead us by foot out of the canyon. We spend our last night on the river sleeping on sand brightened by the glimmer of gold flakes. The next morning, October 27, we roll up the boats, load them onto pack mules from the mining camp, and climb the steep trail back into the world.

Eric's premonition back in Kunming has come partly true. The Shuiluo has proved more jumbled and more difficult than he expected. But with skill and a little luck, we're leaving it alive—if disappointed.

As we cross the narrow bridge over the Shuiluo, I look upriver at the tall mountains we've passed through. From this perspective I can see how far we've come. The river dropped 2,000 feet during our seven days on the water, and we've seen sights no outsider has ever seen. Then I turn my head and gaze downriver, where the Shuiluo twists and narrows into yet another mysterious canyon, disappearing into the unknown.