SuperRoot

Dates and prices

2022

August 6 to 13 ($3,700)

August 14 to 21 ($3,700)

National Observer

First step to preserve the majestic Magpie!! (Read below)

National Observer

September 14, 2017

Valérie Bouchard was in for a special surprise on Thursday evening.

The cancer survivor came all the way from Quebec City to participate in a rally in Montreal to protect the Magpie River, a pristine place in eastern Quebec on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River.The area is known for its majestic scenery, including the hills, the cliffs and the imposing untouched wilderness of the boreal forest. It also holds a special place in Bouchard's heart.And on this hot and humid late summer evening in Montreal, she was able to celebrate an unexpected announcement as the Quebec government's energy corporation, Hydro-Québec, promised to protect the river, abandoning plans for a major hydroelectric development project.Last year, she went on a healing expedition organized by Foundation Sur La Pointe des Pieds for teenagers and young adults who survived cancer. A group of about 16 participants spent a week on the river. They were dropped by a helicopter and rafted down the river. They rafted during the day and camped at night, sharing stories about their ordeals.

"The river, the boat — they're a really a good reflection of life and all the obstacles you can have. You tell yourself in the rapids that you'll never be able to raft through them. But no. We're a gang, we're a team... If we are with a good team, if we have a good attitude with good guides, we can get through all the rapids we need to get through," she told National Observer.

"When I see how important the healing expedition was, (I realized) we need places to be protected and preserved," she said. "The river is good for everyone, not just for cancer survivors. Anyone could benefit from expeditions." Environmentalists celebrate a surprise announcement by Hydro-Québec on Sept. 14, that it won't build a hydroelectric dam on the Magpie River in the eastern part of the province. Video by Clothilde GoujardWe won't touch it, says Hydro-Québec

Hydro-Québec's surprise announcement to abandon plans to dam the popular river followed intensive opposition from environmentalists and some locals from the region.Serge Abergel, manager of public affairs and media for the crown corporation confirmed the news as a flash mob, organized by the Quebec chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), assembled outside the crown corporation's headquarters.

"It is not in our strategic plan anymore. It is not (among) our projects," Abergel said, drawing some cheers from the crowd of about 50 protesters."Be reassured, there is no (hydroelectric) project (for) this river, (and) we won't touch it. We won't go there."

He added this decision was based on the fact that Hydro-Québec was not looking to increase its energy supply at this time. Magpie river, river, Quebec, protected areasEnvironmental groups had previously accused Quebec of blocking the creation of protected areas in spaces such as the Magpie River, featured here in a handout photo. Photo by Charles Kavanagh courtesy of CPAWS CPAWS surprised by victory. CPAWS has been battling for nearly 15 years to put a stop to the project and the crowd was ecstatic, erupting in cheers when they heard the news.Alain Branchaud, director of the Quebec chapter of the conservation group and a former Environment Canada scientist, described the stunning announcement as a victory.

"We are completely surprised," he told National Observer, calling it an "extraordinary announcement."

"We've been fighting for this for the past 15 years and now I think there's a way to make (this protected area) happen in the next months."

Hydro-Québec had previously targeted the Magpie River as a potential development site in a strategic plan of energy projects for 2009-2013. It had estimated that the area could help generate up to 850 megawatts of power. The Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’Environment (BAPE), a provincial organization that holds public hearings to assess the environmental impact of industrial development when mandated by the environment ministry, had previously found a number of reasons why the Hydro-Québec project should be stopped. Among those was an assessment that the proposed development would only produce a modest contribution to the corporation's total generating capacity.

SNAP Quebec, protected area, hydro-quebec, CPAWS. Two protesters dressed as kayakers prepare for a flashmob to ask Hydro-Québec to abandon its hydroelectric dam project on the Magpie river in Quebec. Photo taken on Sept. 14, 2017 by Clothilde Goujard. One of the world's greatest destinations for white-water rafting. National Geographic magazine has identified the Magpie River as one of the world's greatest destinations for white-water rafting. The Quebec Chapter of CPAWS and citizens from the region have also argued that the river can generate economic benefits through tourism in the remote north shore region of Quebec.Their fight to make the Magpie river a protected area is part of a wider CPAWS strategy to increase protection of Canada's biodiversity.

Despite Canada's commitment to protect 17 per cent of land by 2020 under the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, the environmental organization had noted that both Quebec and Canada are lagging behind in their conservation efforts. The province has so far protected 9.35 per cent of its landscape and the whole country is at of 10.6 per cent. In comparison, British Columbia has protected 15.3 per cent of its land and Alberta 12.37 per cent.While this is a "victory" according to Branchaud, he hopes the announcement will push the Quebec government to establish a protected area for the Magpie River.

"Let's go forward and turn Hydro-Québec's disinterest for this river into a political will to create a protected area," he said.

"Now, the main obstacle has just been removed, it's fantastic. We need to celebrate this. But the project of protected area itself is not done yet so we're going keep an eye (on the file) but for us, it's a incredible victory."

National Geographic Adventure

"Viva la Magpie"

By Mark Sundeen

May, 2005

“If the dams are built, it will be like Glen Canyon. People for

generations will be wishing they’d seen it before it was gone.”

- Mark Sundeen, National Geographic Adventure

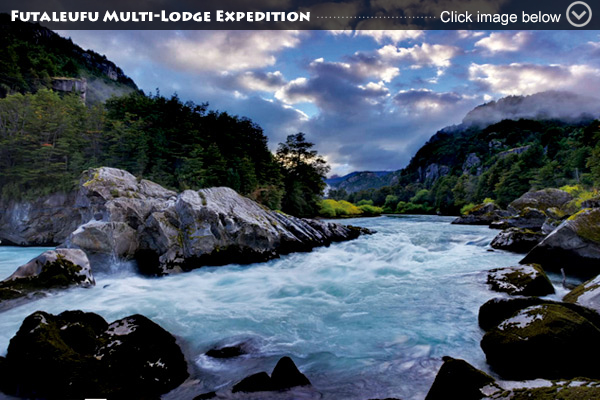

We’re floating down a big North American river, the kind that flows for days with no signs of civilization. Each day without fail more rapids pour off the horizon, black granite lines the banks, and thick stand of fir trees crowd the canyon. But here’s the strange part: Nobody from my 11 years as a white-water guide knows this river, much less has paddles a boat down it. And even though it’s late summer, when the days are long and the water temperatures is mild, we have the place all to ourselves, tearing down rapids so seldom visited they’ve never been named.

The obscurity of the river isn’t the only thing that’s unusual about this rafting trip. For starters, most of our party speaks French and smokes Players. And they keep ducking behind boulders to yap into satellite phones.

We beach the rafts, and the 51-year-old environmental attorney bounds across the talus toward us. He shakes the hand and asks the names of a gaggle of reporters and conservationists- then heads for a picnic set upon a granite slab. Food is served, sat phones are unpacked, and live from the middle of nowhere radio interviews and dictated newspaper columns shoot back to the offices in Montreal.

This little-known place, and the cause of all the commotion, is the Magpie River in eastern Quebec, specifically a series of Class III, IV, V, rapids that rolls down from Lac Magpie (Magpie Lake) and empties into the St. Lawrence River. East and west of its banks is some of the most remote country in southern Canada, a road less and nearly uninhabited wilderness of dense forest. Those hearty enough to carve out a life in these parts- not many – congregate in the string of tattered villages along the St. Lawrence or in the town of Sept-îles, about 90 miles west of the mouth of the Magpie. Even though its mild summer conditions and continuous white water are characteristic of rivers in the lower 48, a raft trop on the Magpie feels remote, wild, more like an Alaska expedition than a guided float some 550 miles northeast of Montreal.

But for all of its one-of-a-kind attributes, the Magpie is, like many spectacular stretches of white water, threatened by a series of dams that would flood its rapids. In response to a governmental energy development initiative, the Montreal power company Hydromega has proposed a dam and generating facility, which as we paddle is under review by Quebec’s Bureau d’Audiences Publiques sure l’Environnment. Kennedy ran a portion of the Magpie with his family three years ago with Earth River on a regular commecial trip and was so taken by it that he has returned in the hopes that his celebrity and his record of river defense (he’s the president of the Waterkeeper Alliance, an international water protection group based in Tarrytown, New York) can help reverse what appears to be a done deal. And so, the thrill of seeing a pristine place is met with the dread that we could be some of the last ones to do so, at least over the portions we’re traveling.

If a destination’s popularity is measured by convenient flights and cute boutiques, it’s clear the Magpie has yet to be discovered. To get within floatplane range, I had to link north-bound Air Canada flights to Montreal and then to a weather-beaten town on the St. Lawrence River, Sept-Îles (Rhymes with “wet eel”) is Canada’s second largest port, the principal interest of which is a massive aluminum smelter on a peninsula nearby. The downtown is a grid of storm proof boxes wrapped in sheet metal, many of them shuttered and closed to business. The night I arrived, I walked down the lonely main drag until I reached a fish-and-chips joint where, trotting out a few tourist phrases in French, I ordered a plate of friend goodies on Styrofoam, listened to the news on French television and watched the rain fall.

Sept-îles and the economically stagnant settlements closer to the Magpie are the kinds of places where power dam proposals are well received. According to Hydromêga president Jacky Cerceau, the Magpie dam will be a boon to the redion, producing 40 megawatts of power that will be used locally and sold on the Quebec grid. Cerceau says that the dam will provide two years of construction work as well as “more than $15 million [U.S. $12 million] in direct financial contributions to the eight municipalities of the region.” Dispersed among 6,000 or so residents over 25 years (after which, says Cerceasu, the dam would be transferred to Quebec’s government), those contributions compute to about $100 (U.S. $81) per person a year. Hydromega’s promises secured the support of the mayors of the local villages, and pending approval from the provincial government, construction could begin as early as this spring.

Perhaps the only folks who don’t applaud the dam are the few who have actually seen the free-flowing river from a boat. Chief among them is Eric Hertz, 49, founder and co-owner of Earth River Expeditions, who has been guiding rafting trips on three continents for 33 years from his home base in New York’s Hudson Valley. When our group met in the lobby of the Hotel Sept-Îles, he look harried, having just driven 15 hours in a mud-splattered pickup truck loaded with coolers of food, four guides and his 12-year-old son, Cade. He began by ordering us to pack lightly, only bringing what was on the list.

“The Magpie is the greatest multi-day white-water river east of the Mississippi,” he told me. “But that doesn’t say it all, because when you think about it, there are no great multi-day rivers east of the Mississippi? It's probably one of the top two or three whitewater river trips in all of North America, after the Grand Canyon. I’d even rank it higher than the Midle Fork of the Salmon.”

Hertz was the first person to take a raft down the Magpie and began running commercial trips on the river in 1990. Intrepid canoeists have known about it for decades, but most are confounded the whitewater and by the expense of getting to Sept-Îles and hiring a floatplane to the put-in at Magpie Lake. The only other way in is to take a northbound train to the headwaters of the Magpie Quest (West) but this approach makes for an additional one-week descent of the 114-mile run, with its numerous Class V rapids, just to get to the standard launch. So in 1989 when Hertz chartered a small plane to take him looking for raftable white water, he believed he had, in the Magpie, discovered a world-class river. His first float confirmed this, but he liked the undiscovered nature of the river for his guests and decided not to advertise it too much. “Earth River has never made much money on the Magpie,” he told me. “But I love it. It’s one of my favorite rivers.” For the past 14 years, he has been the Magpie’s only outfitter, running just two or three weeklong trips a year. He estimates that fewer than 300 people have ever floated it.

Just a week before departure, after Kennedy confirmed his slot, the number in our raft party swelled from 25 to 38 members. So now Hertz was struggling to lighten the load in the baggage boats, one shirt at a time. As he gave instructions to us, he was on the phone hammering out logistics with drivers and pilots who didn’t necessarily speak English. Kennedy was out on a book tour and would be two days late, so Hertz had to coordinate a mid-trip meeting point with the helicopter pilot. Oh, and as long as he was at it, couldn’t the pilot dovetail the Kennedy drop-off with a quick gear haul that would save the team a two hour portage?

It was near dusk when our floatplane landed on Magpie Lake, where four of Hertz’s guides were waiting for us at our first night's camp. In the morning, we paddles across the lake following a faint current that grew and grew until we were running through the Magpie’s first chute, our raft spinning between boulders, the warm water splashing onboard.

The rapids came one after the next, without a guidebook outlining the run. The only other boaters we saw in five days were a crew of four very hearty and somewhat beleaguered canoeists who, like us, had heard about the dam, and wanted to see the Magpie while they still could.

By day three we’re under the Magpie’s spell. The paddling’s great. Kennedy is in the mix. Our spirits are running as high as the white water.

From our picnic spot on the granite slab, Kennedy surveys the river. “Damming this is like finding the ‘Mona Lisa’ in your basement and painting over it,” he says to me between bits of a sandwich. "It’s the unbroken wilderness of the Magpie," he says, "that makes it a superior experience to the Middle Fork of the Salmon.There are no bridges, buildings, and airstrips." Then, abruptly, he stops talking, cocks his ear toward the forest, and says, “I hear an osprey.”

Though he’s here on business, Kennedy can’t wait to get started on the priority stuff: catching fish and instigating water fights with his son Bobby III, 20, and his daughter Kick, 16. That night, when we make camp, he breaks out a fishing rod and recruits a pair of boys from the group. They cast their spinners into an eddy and, with nearly each toss, reel in miniature brookies.

When Hydroméga proposed the dam in 2002, Hertz’s first tactic was direct action. He and his son drove up to Quebec for a public hearing where Cade testified that he’d run the river six times, that is was his favorite, but that he wasn’t allowed to run the Class V rapid at the bottom until he was 13. If it was flooded by a dam he’d never get the chance. Soon Hertz decided that the only way to save the river was to publicize it. He partnered with Alain Salaszius, 46, of the Quebec river advocacy group Foundation Rivières, who had recently appeared on the cover of Sèlection du Reader’s Digest, the French language version of Reader’s Digest , as “The Man Who Saves Rivers.” The two men then brought out the big guns and recruited Kennedy.

While the Canadian press may have cared little about some dam on some distant river, Hertz knew they would pay attention to a famous, idealistic American with an iconic last name. (When Kennedy touched down is Sept-Íles , he was met by reporters from the local paper, as well as a handful of well wishers toting old photos of Kenedy’s late father and uncle: Senator Robert. F. Kennedy and President John F. Kennedy.)

Hertz’s argument is pretty straightforward: The river is worth more as a recreational draw for tourists than as a power generator. Hertz estimates that sometime in the future about 5,000 people a year could float the Magpie. According to the trade group Aventure Écotouisme Québec, this amount of traffic would create $3 million (U.S. 2.4 million) in annual income, which, as Saladzuis points out, is a much larger economic benefit that the promise of 40 megawatts. “If someone promoted its values,” Kennedy says, “this river would produce more revenue and a lot more jobs that building a dam that would make a few people rich by impoverishing this landscape forever.”

It’s unclear, however, if the Magpie could accommodate the numbers envisioned by Hertz. Swarms of black flies might deter visitors in June, leaving about a ten-week season from late July through September when the bugs are mild. To reach the $3 million mark, 70 passengers would need to depart from Magpie lake each day, a spike in usage that could require as many as 15 daily floatplane runs. If the weather turned bad - you’d get a bottleneck of delayed clients back in Sept-Íles. In any case, Hertz says it would be great if many of the outfitters on the Magpie were Quebecers, not only Americans and claims that his business interest is secondary noting that Earthriver split the cost of our conservation awareness trip with a generous client who had done the river and fell in love with it the year before.

The last morning we paddle up to the Magpie’s finale, a 25-foot waterfall just above a Class V rock garden that has a couple of really nasty holes. A few weeks after our trip Earth River sponsored a trip with a small film crew and a group of world renowned kayakers including Steve Fisher to bring an awareness about the river's plight to the kayaking community. The kayakers named this final falls, “Les Chutes d’Eau Eternelles,” or “Eternity Falls,” because it’s the Magpie’s climatic and most menacing drop, and it’s the rapid that would be lost forever beneath the dammed waters.

We line the boat around the falls and then scramble along the bank to scout. A hard rain begins to fall for the first time all week, and coupled with the fog and the foam spraying off the torrent, it feels ominous.

“One time we flipped here with a boat full of lawyers,” Hertz says. "So we jokingly refer to the rapid as Litigation Falls". Nobody responds. To be safe, we’ll run just one craft at a time. A second guide will paddle in each boat, for more control and the other guides will wait at the bottom with rescue ropes.

Hertz’s crew is first. They climb down a slippery granite slab to the raft, which is roped in place in a swirling eddy. When everyone’s seated, Hertz reviews the route, reminds them which way to swim if they end up in the river, then gives the signal to release the rope. The paddlers take a few strokes into the mist and float irreversibly toward a tiny chute above the froth. With a quick forward command from Hertz, they dig in their blades. The raft drops over the horizon, buckles, and its gone. We hurry down the banks to watch the boat as it’s buried beneath the foaming crest of a wave, stalls, and then finally emerges, swamped. The crew lets out a celebratory whoop and paddles safely to shore. One by one we launch our boats, paddle to the brink, then tear down the narrow chute, skirting big, growling pour-overs on either side and exploding into the wave train below. Everyone has a safe run. Soaked to the skin, we celebrate on a flat rock at the bottom, teeth chattering but bodies shot with adrenaline, then load up for the Magpie’s final mile.

Our trip ends at the proposed dam site: a derelict hydroelectric generating station where the Magpie runs under Route 138 before its confluence with the St. Lawrence River. Hydroméga points out that its dam would affect just one mile of the river and the company’s Web site predicts that “the raising of the water level will not prevent sport enthusiasts from enjoying their sport, but rather will improve the access to the area… with the construction of an access ramp along with various paths.” While Hertz and Kennedy admit that this first dam would leave many miles of free-flowing river, they can’t risk it.

“Once the first dam is built,” warns Kennedy, “The next one comes along and you can no longer argue that it will destroy a pristine river. And then you’ve lost the fight.”

In the months after our trip, the battle has simmered on. The Gazette in Montreal issued an editorial condemning the dam. The mayor of Havre-St.-Pierre, a village near the mouth of the Magpie, attacked Kennedy and Hertz and their “little gang of environmentalists” for meddling in Quebec’s affairs, while Canadian conservation groups have launched a Web site (www.magpieriver.com) to organize boaters and activists. Saladzius has been hard at work crafting a new dam proposal that would use the existing structure at Route 138 and not change the river’s flow. Support for this plan, though, has not taken root. In January the mayors of the eight local villages reaffirmed their endorsement of Hydroméga’s dam. Ultimately, the fate of the Magpie is in the hands of the Quebec Ministry of the Environment, which at press time, was at a standstill. A decision is expected this spring.

Whether the result is preordained or not, Hertz believes the Magpie is worth the fight. “This is a river that changes people,” he says. “When they see such a beautiful place and are able to enjoy it with their kids, they are going to want to fight to protect it.”

If the dams are built it will be like Glen Canyon. People for generations will be wishing they’d seen it before it was gone.

National Geographic's Top 10 White-Water Rafting Rivers in the World

(excerpt from From the National Geographic book "Journeys of a Lifetime")

Magpie River, Canada

A float plane takes you to Magpie Lake, the start of this eight-day trip through the remote pine forests of eastern Quebec province. Your first rapids come as you leave the lake for the Magpie River, and from then on they grow in difficulty until you reach the challenge of Class V rapids downriver from the spectacular Magpie Falls. You camp at night on river islands, and to the north you see the pulsating glory of the aurora borealis (northern lights).

Magpie Library

Trip Facts

Notoriety: National Geographic's top ten rafting rivers in the world

Location: 375 miles northeast of Montreal

Access: international flight to Montreal (not included), flight from Montreal to Sept Iles (2 hours) (not included), helicopter to put in (30 minutes)

Nearest international Airport: Montreal

Trip Length: 8 days (Sept Isle to Sept Isle)

Season: August - early September

Included: helicopter to put in, final evening in hotel, all meals from lunch day one until breakfast day eight

Trip difficulty: moderate

Emergency access: helicopter

Experience level: No previous whitewater rafting experience is necessary.

Age limit: 6 to 78 yrs.

Climate: dry, high seventies during day, fifties at night. Can rain with temperatures in the sixties.

Activities/time: rafting & inflatable kayaking (70%), sea kayaking (30%), hiking (5%)

Whitewater: medium to high volume, technical Class 4 (a step up from the Middle Fork of Salmon). Inflatable kayaking rapids, class 2-4 depending upon guest.

Water temperature: Approx. 68 degrees

Wildlife: Moose, woodland caribou, wolf, lynx, bear and osprey

Forest cover: black spruce, white spruce, balsam fir, larch (tamarack) and lodgepole pine.

Elevation: 1,500 feet at put in. 100 feet at take out

Camps: remote beaches and rock ledges

Group size: 18 - 20 (16 person minimum for private departure)

River rafting history: Earth River made the first raft descent of the Magpie in 1988 with Eric Hertz guiding. Earth River began running the first commercial trips In 1990.

Magpie Video

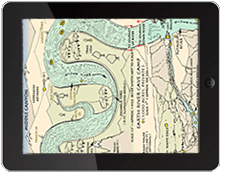

Day by Day

INTERACTIVE ITINERARY:

(click on VIEWS to see photos)

For seven days we explore a wild area few people have ever seen. The whitewater is outstanding and builds in difficulty with the most challenging 4+ rapids coming at the end. For most of the trip, participants will have the option of inflatable kayaking. The rivers numerous class 3 and 4 rapids and warm water make this one of the better inflatable kayaking rivers found anywhere. We will camp on beautiful islands with beaches covered with tracks of moose, bear, wolf and lynx. Clear, star filled nights may include the magical pulsing light of the aurora borealis. Pine trees laden with osprey nests and rocky shores lined with sun-bleached, bone-colored driftwood abound to feed evening campfires. The Magpie's remote falls, deep pools and pristine water make for excellent trout fishing.

DAY 1: SEPT-ISLE / MAGPIE LAKE

This morning we fly (on our own) into the small French-speaking city of Sept-Isle, Quebec where we meet in the lobby of the Chateau Arnaud Hotel. After a trip briefing we board the van for a beautiful one hour drive, along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, past high sea cliffs, remote beaches and impressive waterfalls, to our rendezvous point with the helicopter. One of only two commercially run rafting rivers in the world that are accessed by helicopter, the ride is exhilarating as we glide over remote lakes and wild river canyons through the seemingly infinite, rugged glaciated wilderness that unfolds in every direction as far as the eye can see. We arrive at 30 mile long Magpie Lake where we camp the first night.

DAY 2: MAGPIE RIVER (RAFTING/ INFLATABLE WHITEWATER KAYAKING)

This morning we paddle a few minutes to where the Magpie River spills from the lake. The river is a relatively warm, 68 degrees, due to the top few feet of lake flowing into the river. The day is filled with numerous class four rapids. For the more intrepid in the group there will be a chance to paddle many of these rapids in their own inflatable kayak while being accompanied by a kayak guide instructor who teaches paddling skills and leads the way through the rapids. The terrain varies from old growth boreal forest, to hillsides of thick white lichen, green moss and granite much like Norway. Our final rapid of the day, Marmot (whirlpool), is large, technical 4+. Our night's camps is tucked away in a cove, just below Marmot.

DAY 3: MAGPIE RIVER (RAFTING / INFLATABLE WHITEWATER KAYAKING / STAND-UP PADDLE BOARDING)

Today we run a series a class 4 rapids down to our first impassible class 6 rapid where the guides line the boats around. After lunch we run a few more rapids down to our second class 6 rapid which the guides line the boats around. In the afternoon we float down to camp on a swift current with only riffles. The scenery in this section is stunning, with 1,000 foot walls rising from the boreal forest. There are numerous ospreys fishing in the river. This is the perfect section of river for first timers to try the inflatable kayaks and stand-up paddleboard. We spend the night on a beautiful little island, surrounded by beach, in the middle of a miniature lake. This is the perfect place to try out the stand-up paddleboard.

DAY 4: MAGPIE RIVER (RAFTING / INFLATABLE WHITEWATER KAYAKING / STAND-UP PADDLE BOARDING)

In the morning we raft a series of class 2 and 3 rapids down to 3/4 mile long, class 4, Saxophone Rapid. Above Saxophone is an excellent opportunity for people to try the inflatable kayaks and even the stand-up paddle boards. Above Saxophone, we put people with a little more experience back in the inflatable kayaks. We raft Saxophone down to a beautiful lunch spot on a granite bluff where the river makes two sweeping 90 degree turns affording river views in all four directions. After lunch, there are numerous class 3+ rapids down to a large sand and pebble beach where we spend the night.

DAY 5: MAGPIE RIVER (RAFTING / INFLATABLE WHITEWATER KAYAKING / STAND-UP PADDLE BOARDING) / GORGE CAMP

Today contains the biggest rapids of the trip including double drop (4+), Ledges (4+), 13 foot high Trust Falls (4) and Picket Fence (4+). At nearly a mile long, Picket Fence is the longest, most technical rapid on the river. In the early afternoon we paddle across a lake to the magnificent Gorge Camp for the night. This is one of the most spectacular camps in the world. The camp hangs on the edge of a stunning granite gorge laced with three impassible class 6 cataracts. if there is an aurora borealis that evening it will be in view of the camp, directly over the first falls. The Gorge Camp views are only surpassed by the views from the Falls Camp the following evening.

DAY 6: MAGPIE RIVER (HIKING / SEA KAYAKING / STAND-UP PADDLE BOARDING) / FALLS CAMP

This morning we take one hour hike to the base of the first falls in the gorge. The view is surreal as we stand a mere feet away from the wild maelstrom dropping over one hundred feet in a few hundred yards. There is an incredible place to swim in a calm eddy just below the falls. - While we are hiking and swimming, a helicopter arrives to the camp and portages our camping gear down below the gorge to our final night's camp. Later in the morning we hike down to the end of the gorge and board fast (5 MPH), stable, inflatable kayaks for the two mile lake paddle to the top of 90 foot high Magpie Falls where we eat lunch. Here the entire river hurtles 90 feet of the Laurentian Plateau in a thunderous crescendo of sound and spray. A constant rainbow, rises from the mist and never leaves the falls. We camp on a ledge directly across from the main falls and directly above a second 25 foot falls. This is probably the most spectacular commercial river camp in the world. -- If there is an aurora borealis in the evening, it will be to the north, directly over the falls.

DAY 7: MAGPIE RIVER (SEA KAYAKING / STAND-UP PADDLE BOARDING) / SEPT ILES

This morning we paddle the sea kayaks or stand-up paddle boards down river, with current for 4 miles to the take out where we meet the van. A 45 minute drive towards Sept Iles, takes us to a trail head where we embark on a 1.5 hour R/T hike to spectacular 130 foot high Manitou Falls. In the earlyafternoon we arrive back into at Sept Iles and check into the hotel. That evening we have a farewell dinner.

DAY 8: SEPT ILES / MONTREAL / CONNECTING FLIGHTS

After breakfast, we transfer by taxi (on our own) to the airport for the flight to Montreal and then on to our international flights.

This morning we take a mile hike around the gorge to the sea kayaks and paddle across a three mile lake to Magpie Falls. We camp that night on a flat ledge directly across from the falls. This camp is without doubt the scenic highlight of the expedition. The next morning we sea kayak the final three miles (with current) past smooth granite cliffs and dense spruce forests to the take out. With the vast wilderness to our right and the open St. Laurence to our left, we drive back to the hotel in Sept Iles. That evening we have a farewll dinner.

DAY 8: SEPT ILSES / BACK HOME

Today we take a taxi to the airport (on our own) and catch our flights back home.

Getting there

From the Northeastern and Southeastern U.S. and Europe the Magpie is faster and easier to reach than any multi-day western U.S. river like the Salmon or Colorado.

There are a number of ways of reaching the starting point including flying, driving or a combination of both.

1) Fly to Montreal which has direct flights from many large U.S. cities. Arriving in Montreal, transfer to the 2 hour flight to Sept Ile arriving the evening before and spend the night in a hotel (on your own)

2) Fly to Montreal a day early and spend the evening in Montreal. Catch the early flight up to Sept Iles the following morning to meet the group.

3) Fly to Montreal a day early and transfer to the short flight to Quebec City and spend the night in the beautiful old section of the city. Quebec City is one of the most beautiful and historical cities in North America. Catch the early flight up to Sept Iles the following morning and meet the group.

(NOTE: All flights from Montreal to Sept Iles have a short layover in Quebec City, so a stop over in Quebec City can be arranged through Air Canada at no additional charge)

4) Fly into Montreal and rent a car and drive up to Sept Iles (8 hours). The southern route is relatively flat along the St. Lawrence River and involes taking an hour ferry. The northern route is spectacular with an impressive, mountainous coast line. There are whale watching tours offered near Tadoussac where the Saguenay River meets the St. Lawrence River. Both drives take you past (or through) Quebc City.

5) Drive to Sept Iles from New York: 15 hours, Boston: 13 hours, Washington D.C. 23 hours, Chicago. Although it makes the drive a bit longer, it is possible to visit the spectacular Gaspe Peninsula and Nova Scotia on the drive.

Flight times to Montreal:

New York (1 hour)

Chicago (2 hours)

Washington D.C. : (1.5 hours)

Atlanta (2.6 hours)

Houston (2.6 hours)

Western U.S. Cities (5-6 hours)

London (6.5 to 7 hours)

Paris (7 - 7.5 hours)

Sign up Forms

Trip Documents Below. Please do not fax the forms. Send the originals in the mail.

All Rights Reserved

Copyright © 2020 Earth River Expeditions